Extracting More from a Book with a List than with Zettelkasten

Zettelkasten is a good solution for working with books, but it is not always the best. Let's explore when a list can achieve more.

The title of this material might be as unclear to some readers as it is overly confident to others. First, I propose to explain what Zettelkasten is and then look at cases where a list can be more effective than it.

“Wikipedia” offers the following description [1]:

Zettelkasten (German: 'slipbox', plural Zettelkästen) …often been used as a system of note-taking and personal knowledge management for research, study, and writing.

If you take notes haphazardly and suffer from it, you might want to try this system. It is quite popular and can be maintained in both paper and electronic form.

Although I am deeply involved in activities close to note-taking, this latter has not taken root in me. For some reason, I fall into unbearable despondency at the thought of outlining anything. Meanwhile, I read quite actively, and somehow, I need to work with the book. This is what today’s discussion will be about.

If we again look closely at the definition of the mentioned system, we will find that it is intended for research, study, and writing. That is, for activities in which knowledge accumulates, leading to new conclusions or confirmations of prevailing paradigms. In study, it is useful to learn the material to then perform well on exams. In writing, I also gather materials for the articles I write, so once again Zettelkasten feels relevant.

However, in life in general, do I want to come to new conclusions or confirm the prevailing paradigm while reading a book? Do I want to pass an exam on it? No, I don't. Do I want to thoroughly remember that [2]:

The Church-Turing hypothesis was intended to focus exclusively on issues related to formal mathematical modeling. However, many authors since have interpreted the Church-Turing as if it would set a computation limit for all natural phenomena.

No, I don't. From the morning of August 5, 2024, it is enough for me to remember that any computer, regardless of its power, is fundamentally incapable of reproducing the entire complexity of the human brain. In the context of the current AI boom, this news makes one look at AI differently.

Is it enough to leave only a vague memory from any book? Probably not if all books are read not only for pleasure or broadening horizons. When you want to get more from a book, a more active approach is needed.

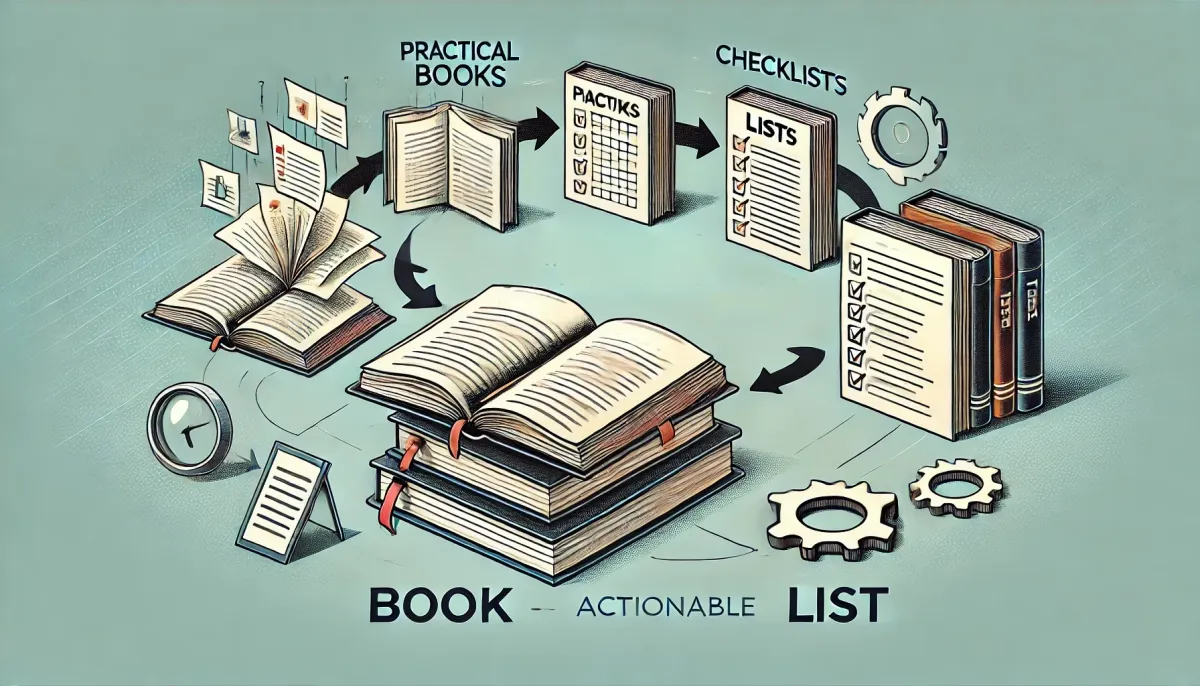

There are books called practical. In Mortimer Adler's work “How to Read a Book” [3], they are defined as follows:

Practical books teach you how to do something you want to do or think you should do.

Those who have read the article about operational definitions might smile a little now.

Can you remember how to do something if you spread the book and its ideas across a group of notes? Maybe you can retell something, but do you have skill now? Did you improve your life? And this blog is precisely about improving the quality of life with lists and checklists. Let’s see using the example of a practical book what to do.

There is a book called “The Healthy Programmer” [4]. As the title suggests, it talks about how to maintain health for those who spend a lot of time at the computer, that is, for programmers. In the summer of 2021, I read it. During the reading, I began to follow one of the recommended practices — conducting a daily health stand-up. That is, a two-minute meeting with myself during which I ran through the following questions:

- What did I do yesterday to improve my health?

- What will I do today to improve my health?

- What blocks me from being healthy?

Fortunately, at that moment, I already had several years of experience with an electronic organizer. Adding another small daily task was easy. Routine running through the questions soon revealed a significant block:

Block: I don’t remember the book’s recommendations.

Something more was needed than notes hidden in the book or elsewhere. Tools were needed that would put health practices at hand.

I took up the book again. It was interesting, not so much to read everything again and remember, as to translate the book into the daily practice. Below, we’ll see what form various recommendations of the book took.

Sitting for hours on a chair is very harmful to health. What can I do about it? I can get up from the chair every time the Pomodoro * timer sounds. How to make it so that the temptation not to get up is reduced? Add looking into the distance during the break. It is good for eyesight, and you cannot do it without getting up from the chair unless there is a window in front of you. An additional reminder in the electronic organizer successfully drives me away from the table.

Regularly drinking water is useful but boring. It’s much more fun to delve into tea culture and travel through different flavors. There’s no need for reminders when there are 40 types of tea in the cupboard.

It’s useful to do exercises for wrists health. But how to remember them? They need to be always visible. No, I didn’t make functional tattoos for myself; I just have a photo cube on the table. It’s always visible, especially when you get up to look into the distance.

The book recommends workouts. In which list do they go? In the to-do list in the electronic organizer. Is this enough? If each task in the list corresponds to a specific time, then yes, it is enough. It’s clear that a workout program is needed, a place, and so on, but we won’t delve into that now.

Modern smartwatches are often equipped with various functions for tracking health indicators. Usually, I look at the daily calories burned during activity. I try to make sure their number is no less than 400.

The last item in the list of elements of my health support system is typing using the piano-playing method from the same book, “The Healthy Programmer”. The author suggests using the experience of pianists who have been studying the issue of hand health for centuries.

In the previous paragraph, I mentioned a list of elements. So, the list itself that we just went through:

- Breaks every 25 minutes according to the Pomodoro system with getting up from the chair.

- Daily constant tea drinking.

- Wrists or back exercises with a cube of exercises as an information radiator.

- Daily exercises, either according to the Adidas program or another program.

- Looking into the distance for 30 seconds, each Pomodoro break.

- 400 kilocalories from the Apple Watch daily.

- Ergonomic keyboard and typing according to the piano-playing method recommended by the book “The Healthy Programmer”.

The discerning reader will notice that not everything in the described system was a list item. Yes, that’s really so. Here it’s worth remembering that a list or checklist is only the beginning. You shouldn’t stick to this tool if there are more effective ones. So what was once an item on the list takes on a physical or other digital form.

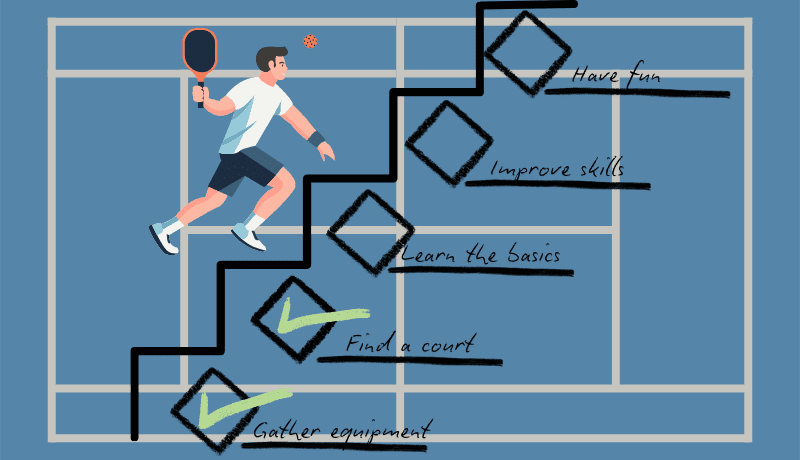

After this extensive example, I return to the original thought of the article. Practical books teach you how to do what is important for our quality of life, and their transfer to another passive format will not bring all the benefits embedded in them. A much more fruitful solution will be to extract a list of practices and start a series of transformations into the form that will bring you the most benefit.

* Pomodoro — a time structuring technique.

List of references:

[1] “Zettelkasten” from Wikipedia

[2] Miguel Nicolelis, The True Creator of Everything: How the Human Brain Shaped the Universe as We Know It, ISBN 9780300248883

[3] Mortimer Adler, How to Read a Book. A Guide to Reading the Great Works, ISBN 978-5-91657-873-7

[4] Joe Kutner, “The Healthy Programmer: Get Fit, Feel Better, and Keep Coding”, ISBN 9781937785314