Top 7 Checklist Mistakes to Avoid for Greater Accuracy and Efficiency

Discover practical tips to avoid common checklist design mistakes that hinder accuracy and efficiency. Read the article to enhance your productivity today!

It’s Not a No-Brainer to Create Checklists

Almost 10 years ago, when reading the “Checklist Manifesto” [1], I expected that in a moment I would become a checklist expert capable of creating great checklists to support my productivity system. This didn’t work as I expected. There was no thorough guidance in the “Checklist Manifesto” book, and in the end, I created my own instruction on how to create a checklist to support your workflow.

It’s not as easy as one might think. During these years, I had a deep dive into management, the Toyota production system, and more. What I haven’t covered yet in this blog are the common mistakes one can make when creating a checklist.

Let’s see some of the most common mistakes. We all know that checklists can build productivity, then increase efficiency, improve quality, reduce errors, and more. But first, we need to design them well.

So, the List of 7 Common Mistakes to Avoid When Creating Checklists

Here comes the list of top checklist mistakes you can make when designing your own:

- Forgetting the purpose.

- Forgetting the end user and context.

- Forgetting end user feedback.

- Making a checklist too lengthy.

- Including unnecessary details.

- Making a checklist too rigid.

- Keeping a checklist outdated.

Forgetting the Purpose

A checklist in general has its purpose. And every particular checklist has a particular purpose. Forgetting the fact that you create a checklist so that its users will achieve a specific goal after the steps are completed is the first and most significant error you can make.

It’s so because the checklist in this case becomes meaningless. There is no path to success if there is no success specified.

Forgetting the End User and Context

Here is an example of a simple checklist:

- Wash hands,

- Wash your face,

- Brush your teeth,

- Put your dress on.

Is it a good one for your child to stick to the morning routine? Well, maybe. But what if your child is 3 years old and can’t read yet? Then it makes no sense to propose a textual checklist. Use a visual one, as proposed in the dedicated blog post.

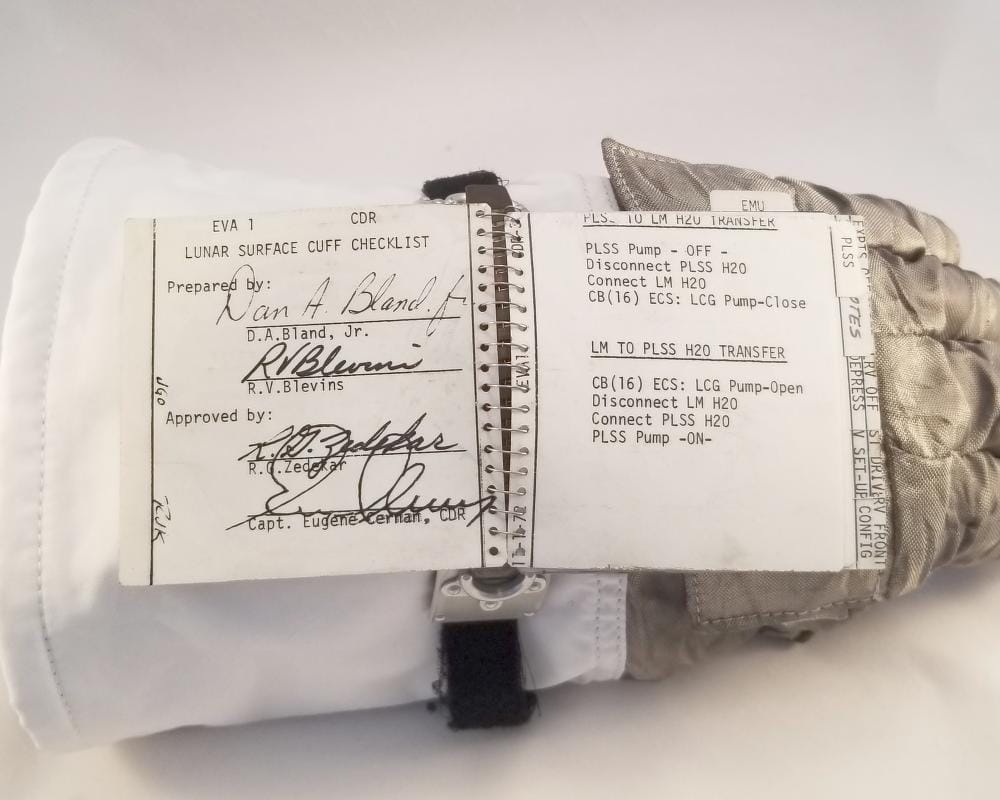

What do you think of checkboxes? Would it be great to add them to your checklist? Not in the case when you are on the Moon. A checklist is a tool, and you need to ensure that it works well for its users.

Forgetting End User Feedback

You might have thought of a user, but did you do the checklist testing and review together? From time to time, life brings more failure “opportunities” than you can expect. A checklist is an instrument, and, like every instrument, it needs testing over the course of its development.

Prior to making it public, ensure that it works well. Don’t forget to continue gathering feedback to make it even more efficient over time.

Making a Checklist Too Lengthy

The optimal length of a checklist depends on the context in which it is used, and thus this mistake is close to the previous one. However, at some point, too lengthy checklists become tedious in any context, and not only in extreme cases.

Those who introduce checklists into work might ask what to do then. The process is complex in the key areas covered by a checklist, and without that many items, it’s not feasible to reach the desired results.

There are solutions. Yes, not only one, but at least three. It’s about “building the checklist into the environment.” You can do this physically. This means that your environment doesn’t allow you to act in a way different from the prescribed. For example, if you want order in your instruments, you can add a checklist to a case where you hold them. Or you can craft sections, as depicted in the image below.

When working on a computer, you have two options. Either this can be the replacement of manual checklist-driven actions by automation, or we can craft a template that is similar to the physical checklist’s transformation.

Including Unnecessary Details. And 👋 to “Checklist Manifesto”

Sometimes the information on a checklist is too specific, and most of the time it brings only confusion but not real help. What could be better than quoting the “Checklist Manifesto” book to show you the example?

Let’s look at the part where Atul and his team decided if it was worth introducing fire-prevention measures into the checklist they were working on:

«But compared with the big global killers in surgery, such as infection, bleeding, and unsafe anesthesia, fire is exceedingly rare. Of the tens of millions of operations per year in the United States, it appears only about a hundred involve a surgical fire and vanishingly few of those a fatality. By comparison, some 300,000 operations result in a surgical site infection, and more than eight thousand deaths are associated with these infections. We have done far better at preventing fires than infections. Since the checks required to entirely eliminate fires would make the list substantially longer, these were dropped as well.»

So the infection rates were much higher than fire-related problems, and it would be better to concentrate on how to prevent them to improve the quality of surgery worldwide.

Making a Checklist Too Rigid

You can classify checklists differently, and one way is to distinguish action and inspection checklists. Usually, you want to use an action checklist (also known as “READ-DO”) when it’s easy to misstep, and guidance along the way would be good.

Inspection checklists (“DO-CONFIRM”) give people more freedom in how they progress towards the goal. It’s a way to confirm that the goal is achieved.

Don’t use rigid checklists where flexible ones work well. People tend to dislike too narrow borders, and you would rather not overcome the additional resistance that happens when the checklists are introduced.

Keeping a Checklist Outdated

In the IT world where I am from, it is ubiquitous when you come to a new place and meet outdated documentation. You start doing things and try to follow the instructions. But first this doesn’t work, and then that doesn’t work. In the end, you navigate to an experienced local software engineer, and you start pair problem-solving “procedure”.

As you might think, many benefits that documentation gives to you are gone in such a situation. I call this unfortunate situation that might happen to any company informational shizophrenia. Data tells you one thing, and people tell you different things.

For the checklist, the problem is even more significant than for a document. Because it’s not some random piece of text just FYI. It’s an actionable instruction, a path to some goal, sometimes even a critical one. If its key points are incorrect, it will lead you to the wrong outcomes.

Conclusion. Checklists Worth Your Accuracy

At first glance, checklists might seem like something easy as writing on a piece of paper. No, it’s a tool to prevent human error. Put yourself in a situation when people around you plan to apply the following steps [2]:

- Doctors wash their hands with soap.

- Clean the patient’s skin with chlorhexidine antiseptic.

- Cover the patient with sterile drapes.

- Doctors should wear a mask, hat, gown, and gloves.

- Place a sterile dressing over the catheter site after the line is inserted.

It is a checklist proposed by Peter Pronovost to reduce the number of arterial line infections. Here are the results of it being applied for more than a year at Johns Hopkins Hospital:

The checklist prevented 43 infections and 8 deaths, the infection rate dropped from 11% to 0%, and saved the hospital $2 million.

I think that you agree with me that you would want to have the best possible checklist crafted, as well as applied as carefully as possible.

List of Links

[1] Atul Gawande “The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right”, ISBN 978-0312430009

[2] “The Negative Checklist: Reducing Errors” from the “Novel Investor” blog